The Arcana arcanissima is divided into six books, which give a clear sense of Maier’s beliefs about the

underlying message of ancient myth: 1) On the hieroglyphical Egyptian gods (Osiris, Isis, Mercury, Vulcan,

Typhon, etc.) and the mythic activities and characters of singular creatures; 2) On the allegories of the

Greeks, primarily those involving golden objects such as Jason’s golden fleece and the golden apples of the Hesperides; 3) On the

fictitious, philosophical or chymico-medical golden genealogy of gods and goddesses; 4) On festivals, holy

occasions, and games, instituted in honor of this science; 5) On the labors of Hercules and their meanings in

relation to the art of alchemy; and 6) On alchemical interpretations of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Maier is careful to criticize paganism and to emphasize Christ’s role as the true Savior Physician, but he nevertheless emphasizes the value of the chymical secrets lying behind the myths. He repeatedly reminds his

readers that these tales should not be taken as histories but are instead hieroglyphs or allegories, that is,

tales “concealing some deeper meaning, philosophical or moral, which must be withheld from those persons too

ignorant or too impious to use it aright.”

According to Maier, the Egyptian priests transmitted their knowledge of the chymical artifice in this way so as

to only reveal it to the most worthy. As a devout Lutheran he avoids mentioning Catholic fourfold exegesis of scripture in support of this multilayered

reading, but discusses

instead the accustomed fourfold reading of the works of Homer, with hieroglyphical, political, poetical, and

grammatical levels of consideration. The ancient Roman scholar Marcus

Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) is also mentioned as one who spoke of almost all the classical gods as “elements of

the macrocosm” (thereby tacitly renouncing a plurality of gods), with Saturn, for example, representing the

Heavens or Form, and Rhea the Earth or Matter. Suda's belief that the Golden

Fleece was a “book or membrane containing Chrysopoeia” is introduced into the argument. But the “most

secret secret” is that mythology is all about chymia, transmitted by means of hieroglyphical letters or pictures

of animals from the Egyptians to the Greeks, and the truest interpretation is that it all concerns the

“Philosophical Medicine,” the “golden Medicine, acting as golden medicament of the body and spirit.”

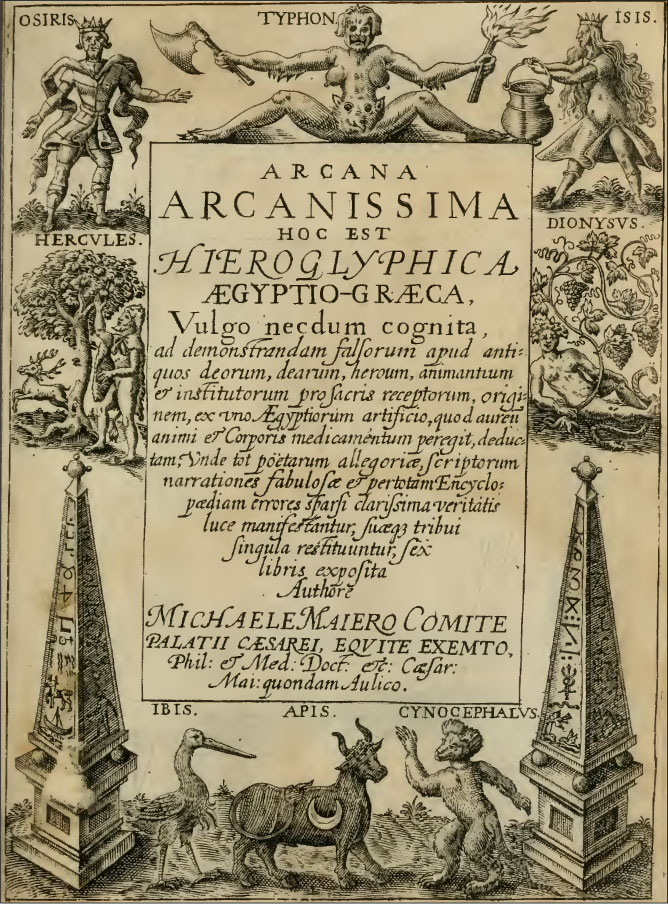

Maier introduces his reader to the four principal “Hieroglyphical Gods of the Egyptians” — namely the brother and sister Osiris, or the

Sun, and Isis, or the Moon; “Mercurius,” who joins with the Sun and Moon as common to

both; and finally the “burning spirit” Typhon (i.e., Set), not classed as a god but as a malign demon, who

chopped his twin brother Osiris into “most fine parts” (tenuissimas partes). In addition to

these four, Maier lists a decidedly Latin-sounding group of Egyptian deities: Vulcan (external fire), Pallas

(Wisdom of Operating), Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, Apollo, Pluto, and others. Elsewhere Maier introduces Horus as

one of the most ancient gods, preceding a list of twelve Greco-Roman deities, six male and six female, with

reference to the mythographer Natale Conti. Maier argues that the ancient poets

wanted to show that “those Gods did not exist, except as fictitious [and] imaginary, but were symbols and

emblems, some for the eye, others for the mind, hidden to the vulgar, but known to themselves.”

Maier is most interested in the “Chymical Gods” (Dij Chymici), or indeed the “principal intellectual chymical

gods” (praecipui dij intellectuales chymici): Osiris, Isis, Mercurius, and Vulcanus, who are not

celestial but rather subterranean, born of the art. Egyptian Isis is identified as Greek Ceres and Osiris as

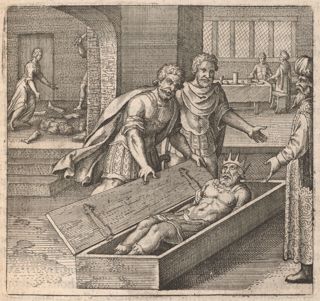

Bacchus or Dionysus, “chief of the golden gods” (aureorum deorum primarius). Osiris

is explained to symbolize the “matter of the art, from which the golden Medicine is composed”; his death

represents the alchemical process of “solution”; the tomb in which his dismembered body is placed by the “fiery

and furious spirit” (spiritus igneus & furiosus) Typhon is the alchemical vessel. After this

solution, Isis collects the parts and unites them with combustible sulfur, such that the soul of Osiris becomes

sufficiently ardent that he converts Isis, mother‑wife‑sister, into himself, resulting in the ultimate

hermaphroditic or androgynous perfection.

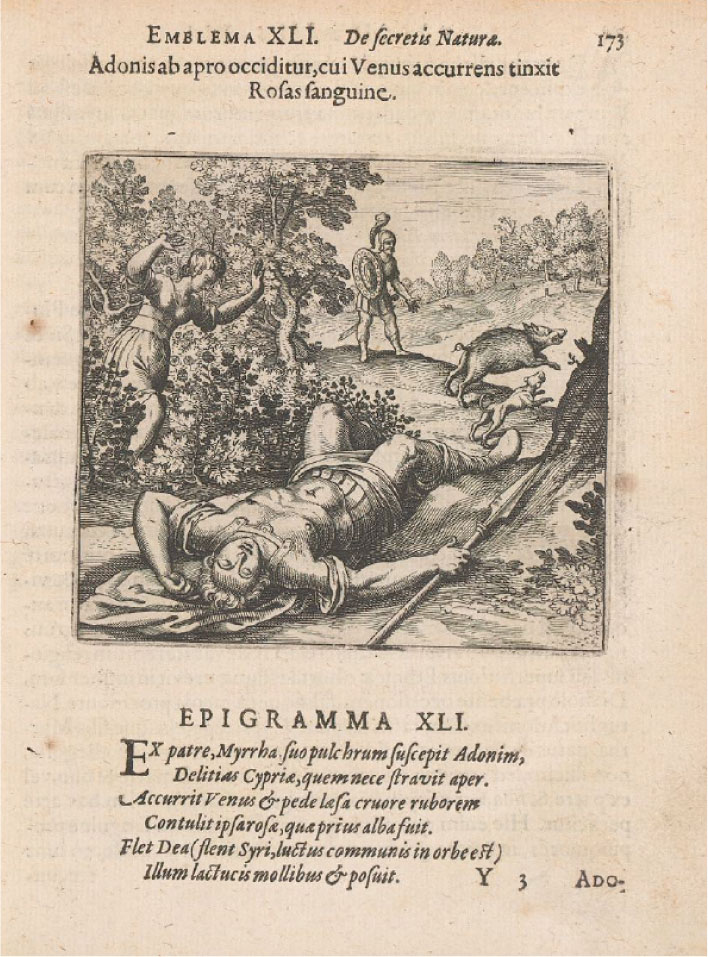

The Arcana arcanissima contains a multitude of alchemical interpretations of mythological motifs; here,

a scant few will have to suffice. On the grounds of Egyptian myth, the “black bull” Apis is “a hieroglyphic and

indubitable character of the true and unique Philosophical Matter,” the “Chaos philosophicum,”

containing all things. This is backed up with reference to Greek motifs, from the bulls of Minos; the story of

Theseus, Ariadne, and the Minotaur in the Cretan labyrinth; Hercules’s fight with the three-bodied (or

three-headed) giant Geryon; and Jason’s yoking of the fire-breathing bulls.

The god Pan, as well as the satyrs, including Silenus, companion of Dionysus, represent the “vileness, wildness,

or rawness of philosophical matter.”

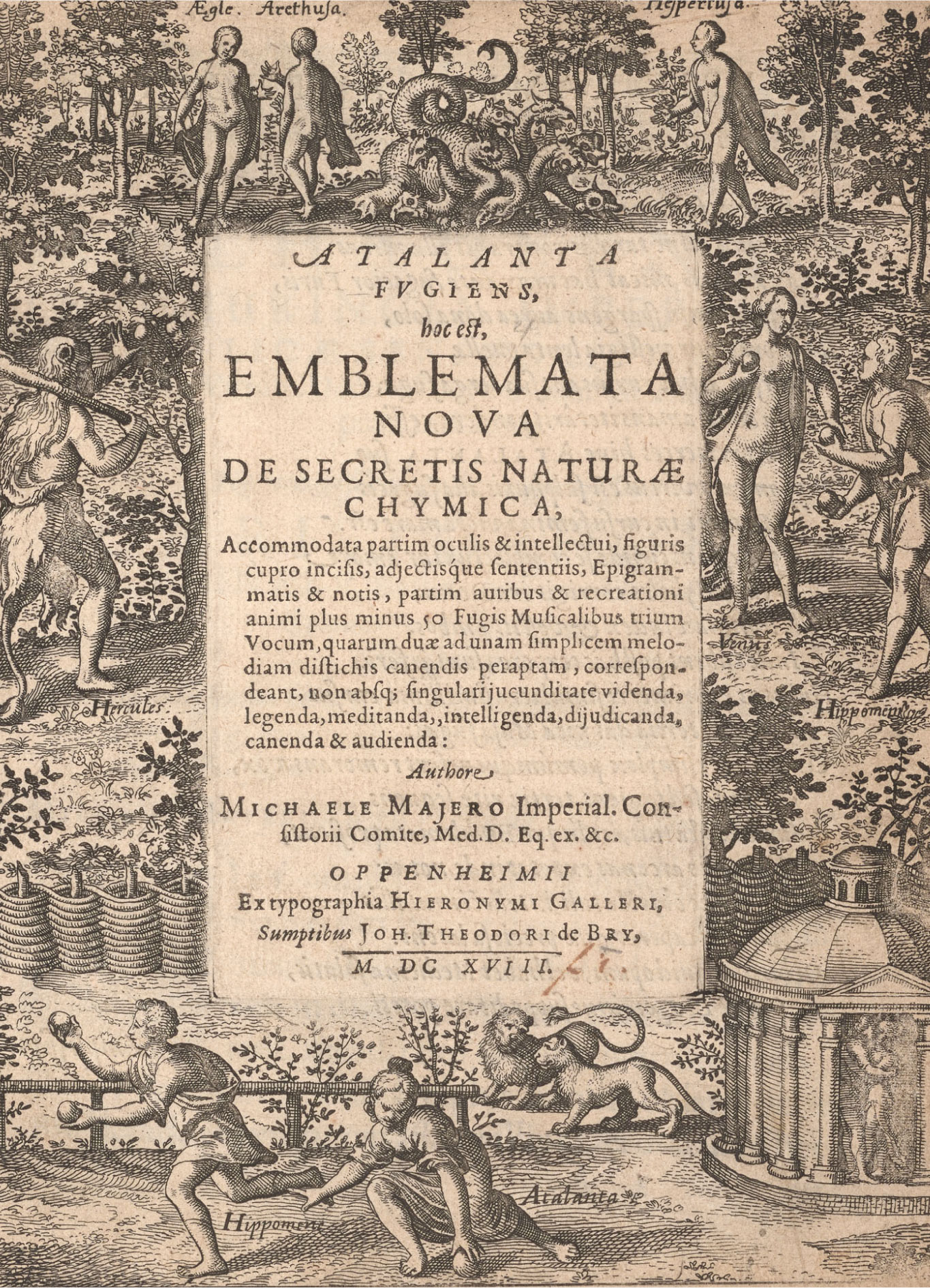

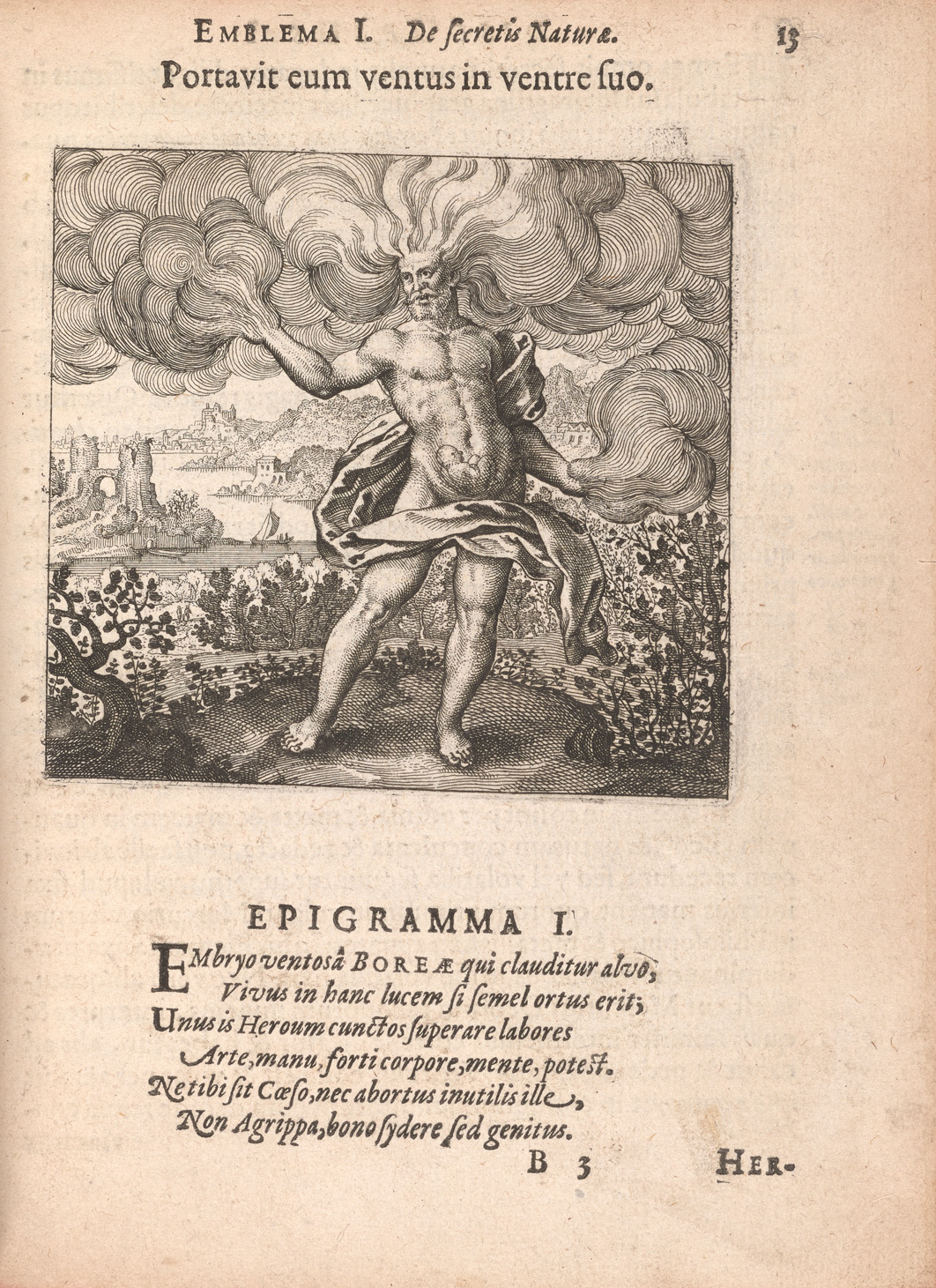

The “story of the birth, struggle and victory of Dionysus graphically depicts the whole Philosophical artifice,”

hence his appearance on the book's title page.

Osiris’s deadly brother Typhon has an affinity with serpents and dragons, which is “proven” by Maier through the

anagrammatical “transposition” of the letters of his name to “Python,” adversary of Apollo.

Alchemically, Typhon represents “that foetid water that putrefies,” a “sulfurous and burning spirit,” while his

wife Echidna denotes the “watery and cold flowing substance,” that is, quicksilver.

From their union arise the various mineral species, represented by their large brood of monstrous offspring,

including Cerberus, the Sphinx, Chimaera, Hydra, and the hundred-headed dragon Ladon, guardian of the golden

apples of the Hesperides.

Much is said concerning Mercury, inventor of letters, numbers, and musical instruments and intervals, as well as observer of

the courses of the stars and psychopomp. While the lame god of the

forge, Vulcan, is associated with fiery lions, Mercury is connected with dragons and serpents, such as the male

and female snakes entwined around his caduceus. The wand represents his

marvelous ability to reduce all dissident things to concord, whence the famous alchemical dictum Est in

Mercurio quicquid quaerunt sapientes (There is in Mercury whatever the wisemen seek). In

line with a multitude of other alchemists, Maier considers Mercurius to be the “subject of the chymical art,”

indeed describing him with the extremely Christ-like epithet “Omnia in Omnibus” (All in All

things).

In an entertaining piece of cod-etymology, we discover that the Egyptians called Mercury in their tongue

Theut, with whom the Germans are connected, calling themselves “Theutonos sive

Theutschen” (Teutonic or Deutsch).

Another major figure in Arcana arcanissima is the demigod Hercules, son of Zeus and Alcmene, famous

for his twelve labors. While his father represents the internal agent of the art, its principal subject, Maier

explains that Hercules is the external agent, the artifex himself. A whole book is devoted to

the chymical interpretation of the labors of Hercules, many of which easily connect with traditional alchemical

symbolism. His first task was to slay the Nemean lion, which was neither Asian nor African but celestial and

ultimately alchemical, with Maier adducing the Green Lion of the Rosarium philosophorum (Rose garden of

the philosophers; 1550), Senior’s parable of the hunting of the lion, and the explanation in the Consilium conjugii (Advice on the conjuction) that Leo is the Sol inferius (lower sun). Hercules’s combat with the watery serpent, the Lernaean Hydra, is likewise identified as alchemical, with Basil Valentine’s

De occulta philosophia (On occult philosophy) cited for its reference to Mercury as a serpent from

waters. In a similar fashion, Hercules’s task of obtaining the golden apples of the Hesperides, guarded by the hundred-headed dragon Ladon, is another labor

amenable to alchemical interpretation.

Maier in fact identifies three Greek heroes as representatives of the alchemical artifex: Hercules, Jason, and

Odysseus. Jason’s quest with the

Argonauts for the Golden Fleece, interpreted as “the Philosophical Stone, the highest medicine of human bodies,”

is one of the best-known myths.

Maier explains that Jason was assisted by the sorceress Medea, who made four potions (pharmaca): 1) an

unguent that protected his body from the dragon’s lethal fire and venom, as well as the fiery breath of the

bulls; 2) a soporific narcotic to put the dragon to sleep so that he could steal the fleece; 3) a limpid water

that extinguished the bull’s fire; and 4) a special image of the Sun and Moon, which he wore around his neck, for

success in the work.

In keeping with his insistence that true chymia concerns the Golden Medicine, Maier etymologically presents

Jason’s name as a fitting example of nominative determinism: “for the name expresses healer, from

Iasthai or healing; for Iasis is the art of healing.”

Jason, like Hercules, was educated in healing by the centaur Chiron, from whom he gained manual experience, just

as he gained the necessary advice and theory for the perfect completion of the work from Medea. Jason represents

the “Medicus Philosophus,” while Medea represents “most outstanding assistance,” or reason.

The Golden Medicine, like that prepared by Medea, included the powers of rejuvenation. Maier’s

reading of myth was thus not only a source for examples of interactions between alchemical substances but also

concerned the relationship between theory and practice. Again, Maier could cite alchemical authorities, such as

Pseudo-Lull’s Testamentum (Testament), in support of his allegorical

interpretations, for example “the Dragon, i.e. Fire, in which is our golden Stone, lives in all things.”

Only someone blinder than a mole, Maier argues, would not see that these are all chymical fables.

In the beginning of 1616 Maier returned to the continent, and the next few years were to see a flurry of

publications. In 1616 he published De circulo physico quadrato, hoc est, auro eiusque virtute

medicinali (On the natural circle squared, i.e., Gold and its medicinal virtue), closely followed by

Lusus serius, quo Hermes sive Mercurius rex mundanorum Omnium, &c. judicatus & constitutus (A serious

jest [or game], by which Hermes or Mercurius is judged and appointed king of all worldly things, &c.). Neither of these works was as intent on mytho-chymia as the Arcana arcanissima,

but both include mythological references.

The following year, in 1617, there appeared the Examen fucorum pseudo-chymicorum (Swarm of

pseudo-chymical drones).

There we find one or two mythological references — for example, one to Saturn throwing up a stone that he had

previously swallowed thinking it was his rival Jupiter, and another to the golden apples of the

Hesperides — although the focus of the work is a criticism of fraudulent alchemical practice, for which he borrows heavily

from Heinrich Khunrath’s pseudonymous Treuhertzige Warnungs-Vermahnung (Sincere warning-admonition),

appended to Vom hylealischen Chaos (On primaterial chaos; 1597).

Published around the same time, the Jocus severus (A serious joke; 1617) is an allegorical account of

a tribunal of birds set up to judge the Night Owl (Noctua), associated with the goddess of wisdom and for Maier

a symbol of Chemia. Again there are brief references to myth,

one from the mouth of the Swallow (Philomela), doubtless emboldened by the criticisms of Natale Conti, claiming

that chymia is full of fables and that those of the poets concern hidden chymical matters rather than moral

lessons.

Then followed the Symbola aureae mensae (Symbols of the golden table; 1617), introducing a cosmopolitan

lineage of alchemists from twelve different nations, ranging from the Egyptian Hermes Trismegistus in antiquity

to the modern “Anonymous Pole,” Michael Sendivogius (1566–1636).

Contrary to his treatment of the ancient gods, who are explained as fictions, Maier emphasizes that Hermes

Trismegistus was most definitely not a “fictitious person” (personam fictitiam) but a most ancient

Egyptian philosopher. In his discussion of Hermes,

Maier returns to material discussed in Arcana arcanissima, including the myths of Apis, Osiris, Isis,

and so forth as representatives of the Egyptian chymical gods; he references in particular the myth of the

Golden Fleece, with Jason as the “physician with subtle stratagems” and Medea as “Counsel of Theoretical

Reason.”

While happy to discover chymical truth in pagan mythology, and indeed to go along with those, like Lodovico

Lazzarelli (1447–1500), who find a Christian message in analogical readings of Hermetic works, Maier criticizes

those who “most impiously and sacrilegiously” attempt alchemical readings of the “Creation of the world,

nativity, passion, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ.”

Another of Maier’s publications from the same year may help explain this stance. In 1617 Maier published his

first apologia for the Rosicrucians, Silentium post clamores (Silence after the clamors),

following the appearance of the three Rosicrucian manifestos Fama fraternitatis (Rumor of the

brotherhood; 1614), Confessio fraternitatis R. C. (Confession of the brotherhood; 1615), and

Chymische Hochzeit (Chemical wedding; 1616).

The Fama explicitly condemns “books and figures [that] have been brought out under the name of chymia,

which are in Contumeliam gloriae Dei [an insult to God’s glory].”

Similar sentiments are expressed in the Confessio: “we must earnestly admonish you, that you cast away,

if not all, yet most of the worthless books of pseudo-chymists, to whom it is a game to apply the Most Holy

Trinity to vain things, or a joke to deceive men with monstrous figures and enigmas.”

The same point is driven home in the Chymische Hochzeit, when the pseudo-chymists are separated from

true practitioners: “[Y]ou have forged false and spurious books, fooled and swindled others, thereby lowering the

royal dignity in everyone’s eyes. You also know what blasphemous and seductive pictures you have used, sparing

not even the Holy Trinity, but using it for the cozening of one and all.”

While Maier was comfortable with making references to the chymical significance of the Egyptian gods or of Hercules and Jason, his admiration for the Rosicrucian message must have convinced him to avoid drawing

analogies between the philosophers' stone and Christ. Perhaps, like the

Catholics Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) and Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655), he was concerned that such practices risked distorting scripture,

“pass[ing] off the mysteries of our faith as natural things,” or making “alchemy the sole religion, the

alchemist the sole religious person, and the tyrocinium of alchemy the sole catechism of the faith.”