Primary Sources

Agrippa von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius. De occulta philosophia libri

tres. Cologne, 1533.

August II, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Wolfenbüttel. Gustavi Seleni

Cryptomenytices et

cryptographiae libri IX. [Lüneberg], 1624.

Of the advancement and proficience of learning. Oxford, 1640.

Cardano, Girolamo. De rerum varietate libri XVII. Basil, 1557.

della Porta, Giambattista. De furtivis literarum notis. London, 1591.

de Vigenère, Blaise. Traicté des chiffres, ou secrètes manières d’escrire.

Paris, 1587.

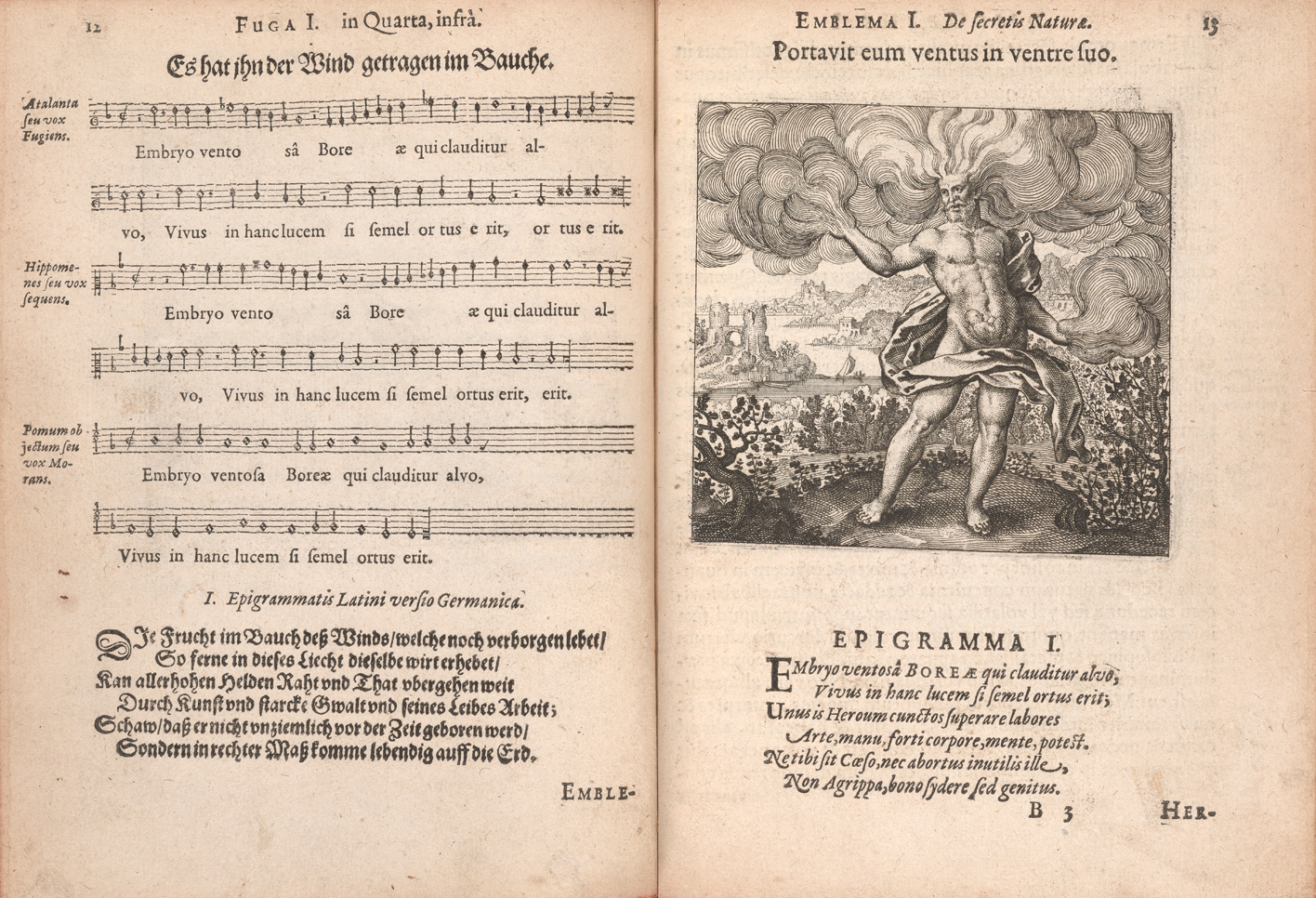

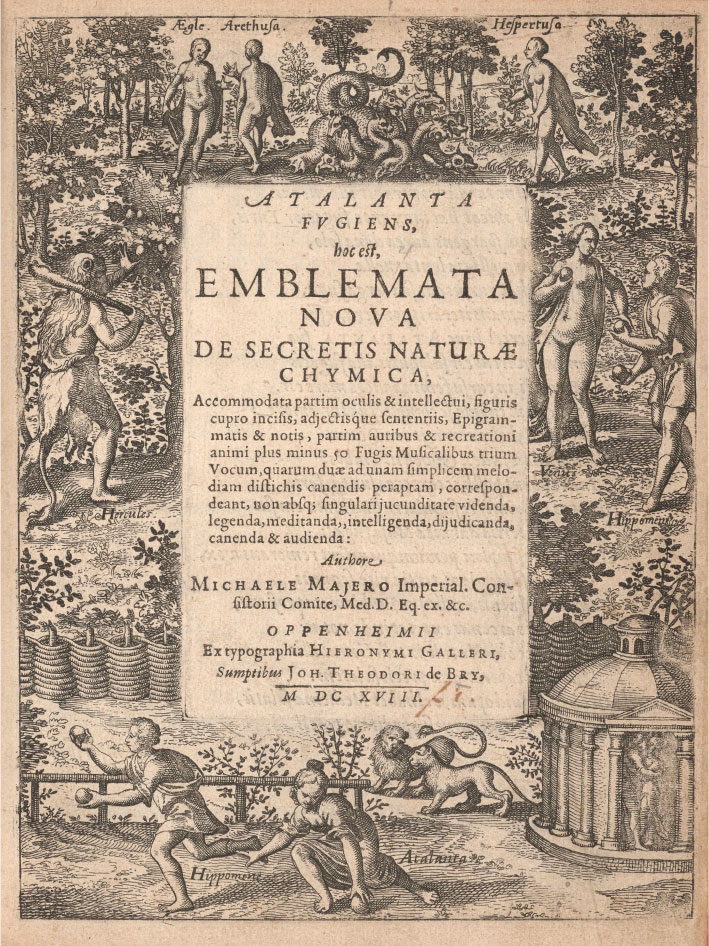

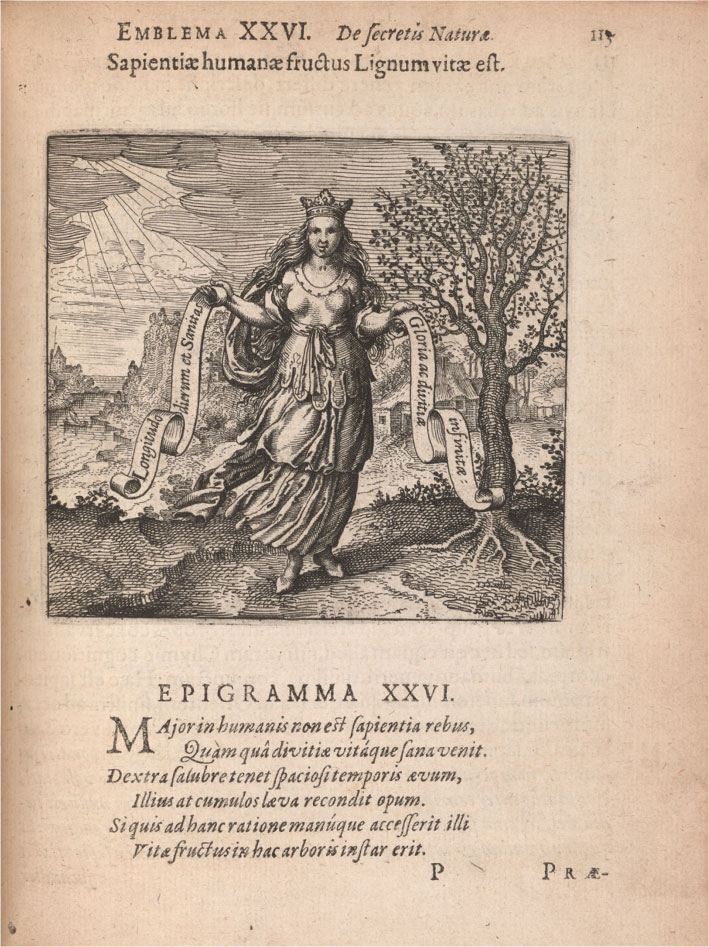

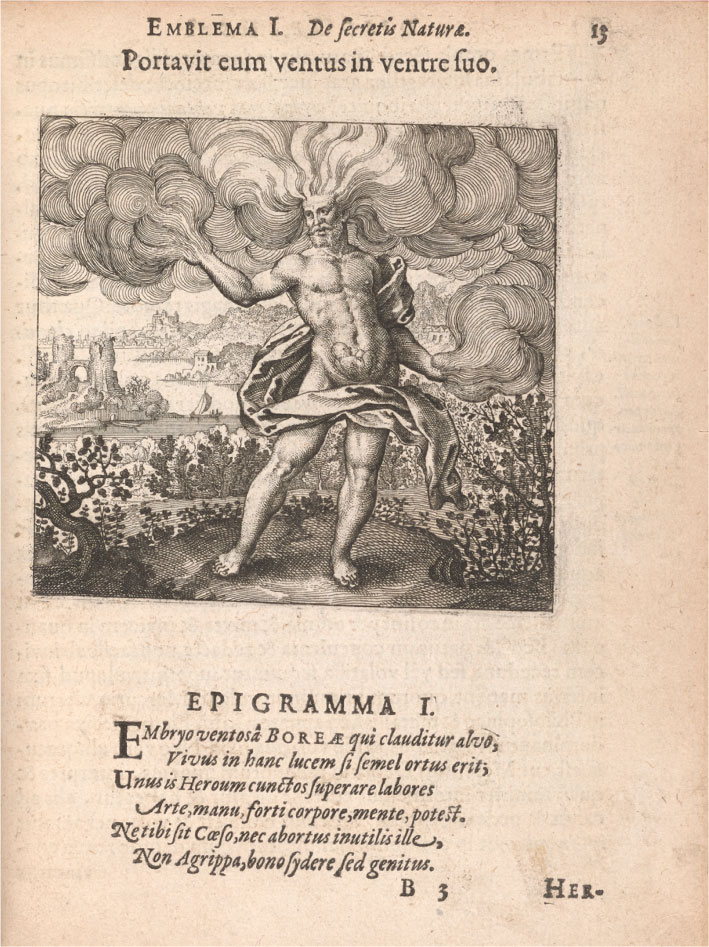

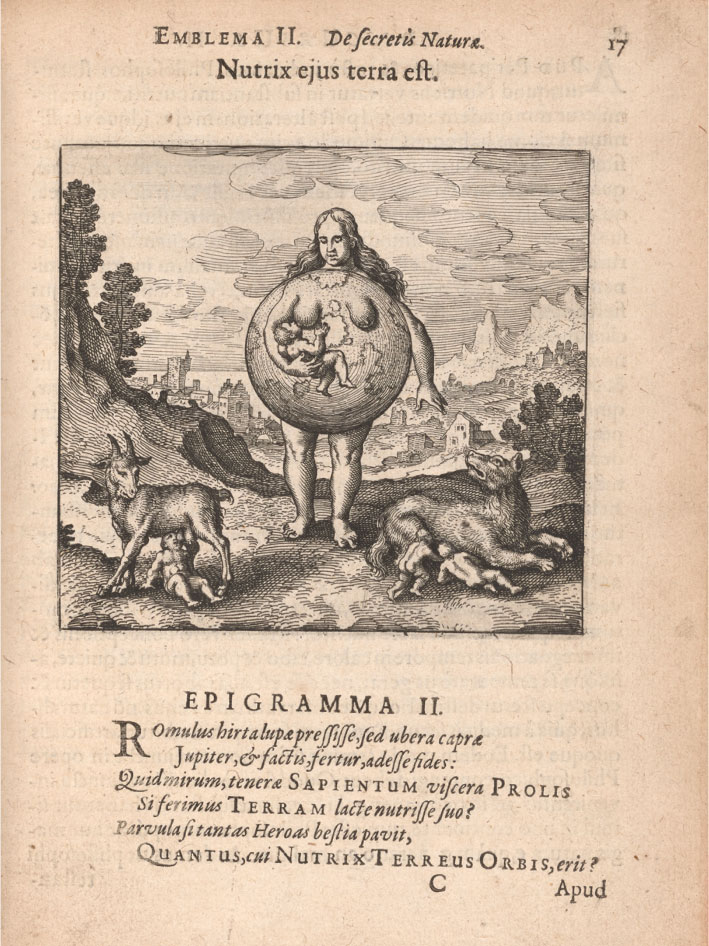

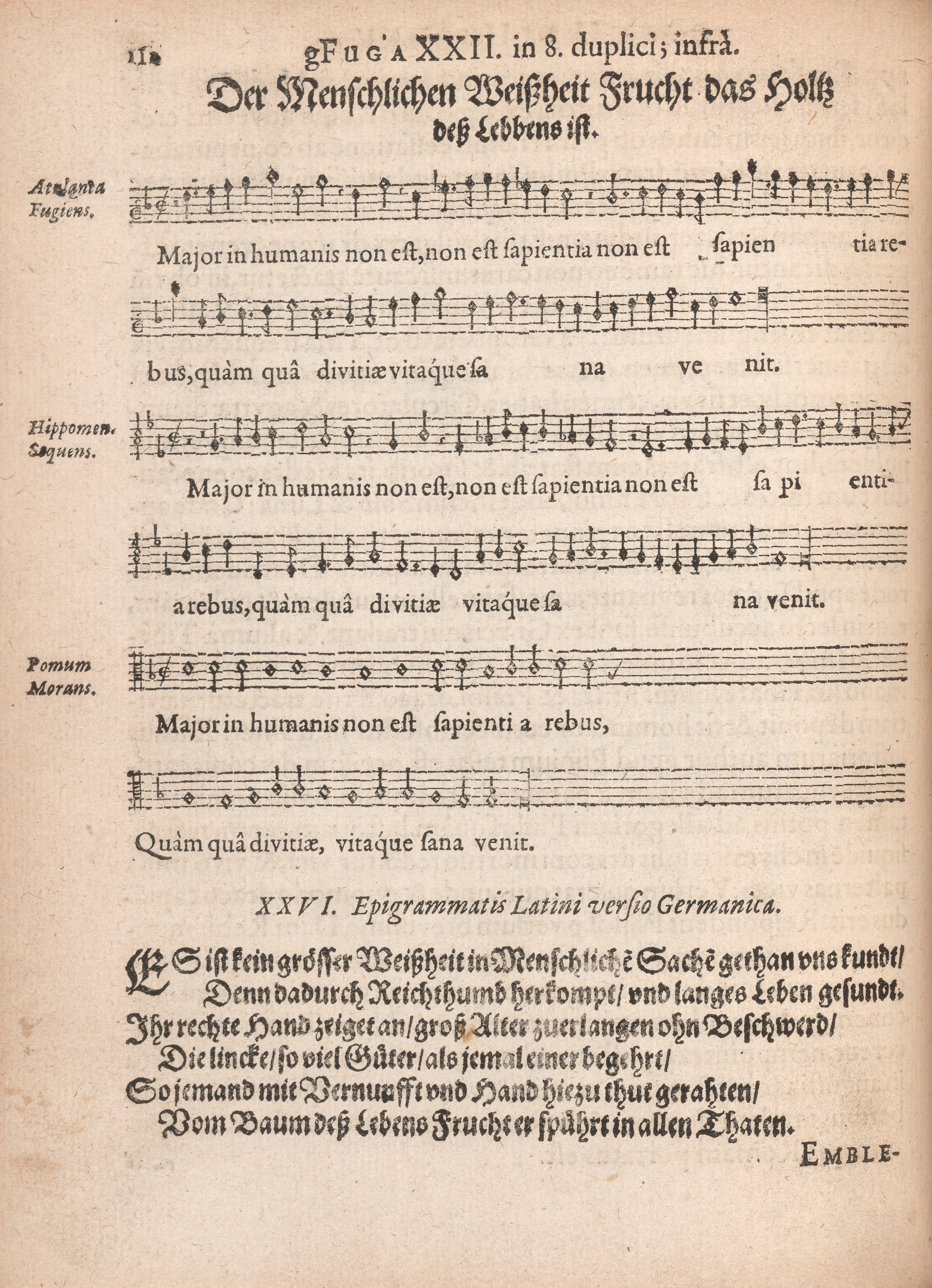

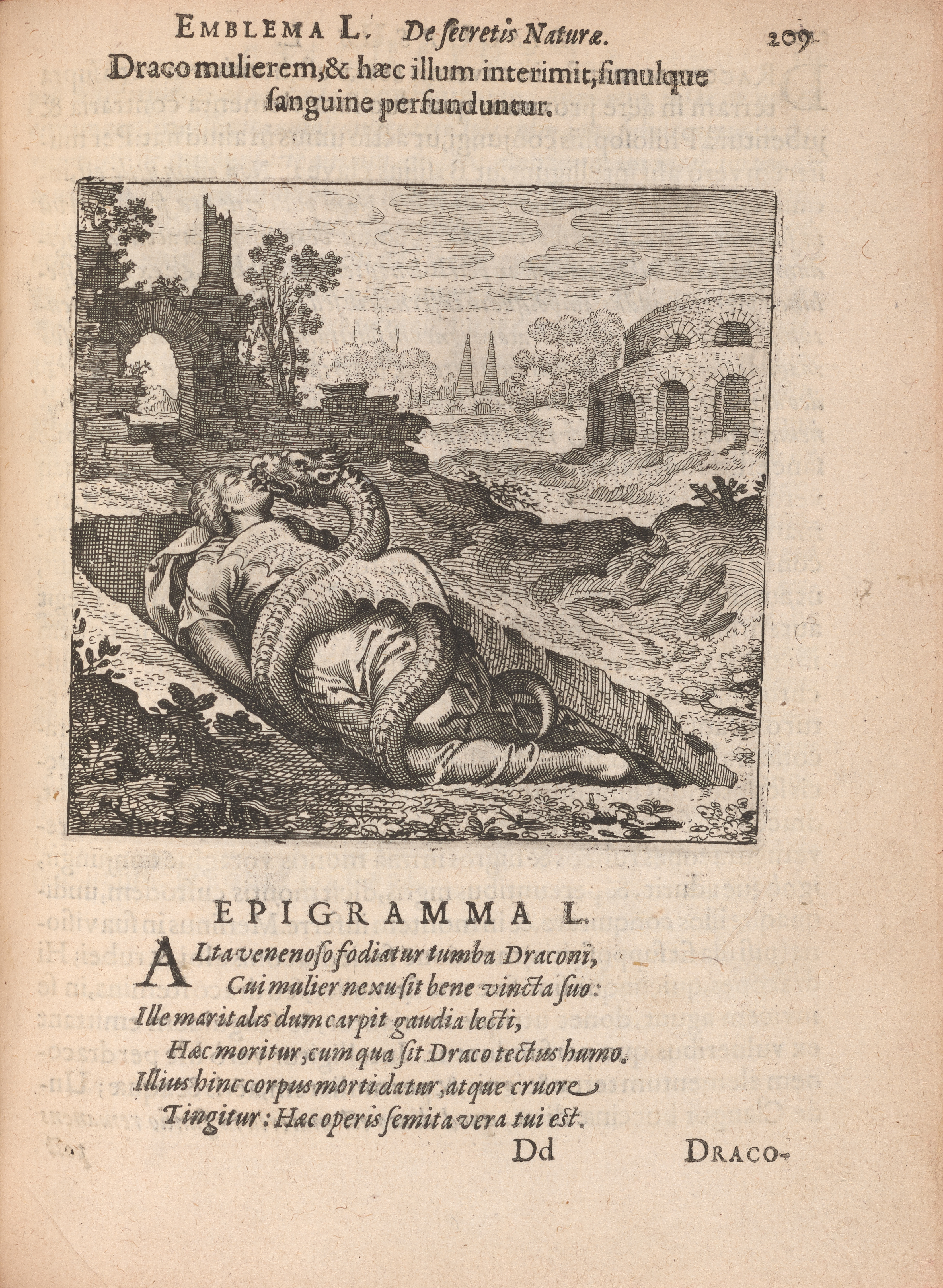

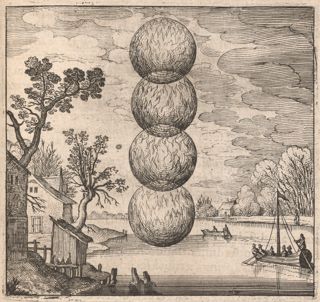

Maier, Michael. Atalanta fugiens: An edition of the fugues, emblems, and epigrams by

Michael Maier.

Edited by Joscelyn Godwin and Hildemarie Streich. Grand Rapids: Phanes Press, 1989.

Atalanta fugiens, hoc est, emblemata nova de secretis

naturae chymica. Oppenheim, 1618.

“Atalanta running, that is, new chymicall emblems relating to the secrets of nature.” 1618

or after. Mellon Alchemical Collection 48. Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Secretioris naturae secretorum scrutinium chymicum. Frankfurt, 1687.

Raasveld, Paul P., ed. Emblem Books with Songs and Music. Leiden: E. J.

Brill, 1999.

Trithemius, Johann. Polygraphia libri sex. 1518. Reprinted, Strasbourg, 1600.

Steganographia. N.p., ca. 1499. Reprinted Frankfurt,

1608.

Wilkins, John. Mercury; or the secret and swift messenger. London, 1641.

Secondary Sources

Adams, Alison, and Stanton J. Linden, eds. Emblems and Alchemy. Vol. 3 of Glasgow Emblem Studies,

edited by Alison Adams, Laurence Grove, and Amy Wygant. Glasgow:

University of Glasgow Department of French, 1998.

Bilak, Donna. “Alchemy and the End Times: Revelations from the Laboratory and Library

of

John Allin, Puritan Alchemist (1623–1683).” Ambix 60, no. 4 (2013):

390–414.

Blair, Ann. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern

Age. New

Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Brann, Noel L. Trithemius and Magical Theology: A Chapter in the Controversy over

Occult

Studies in Early Modern Europe. Albany: State University of New York Press,

1999.

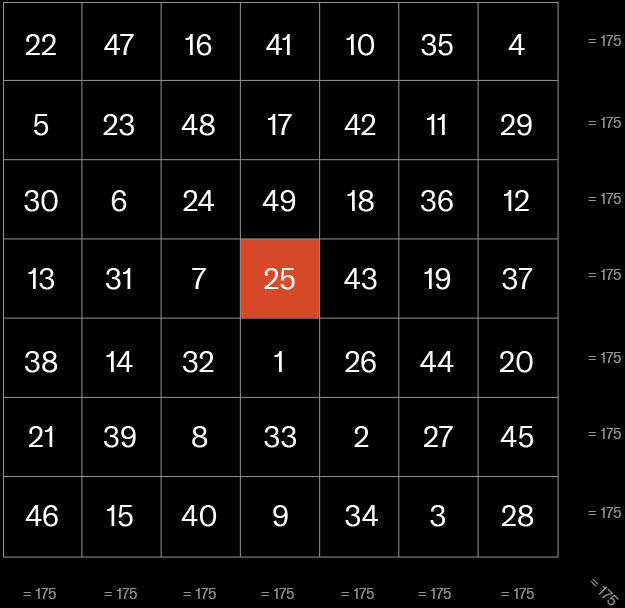

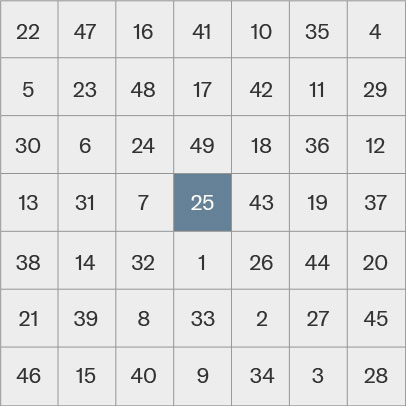

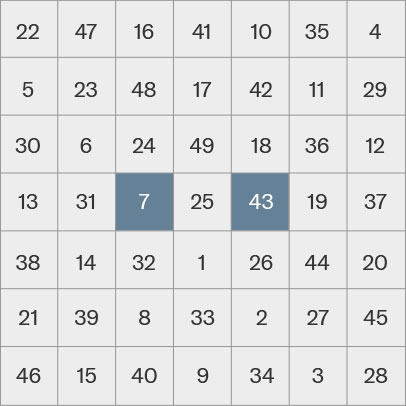

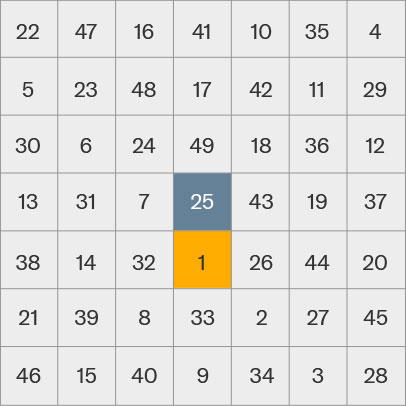

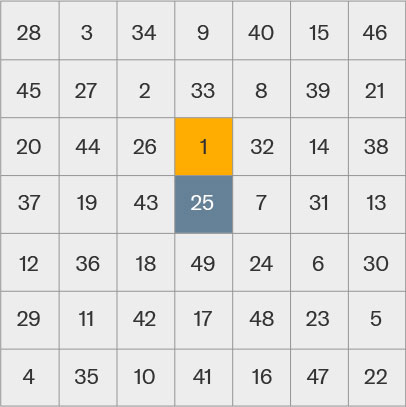

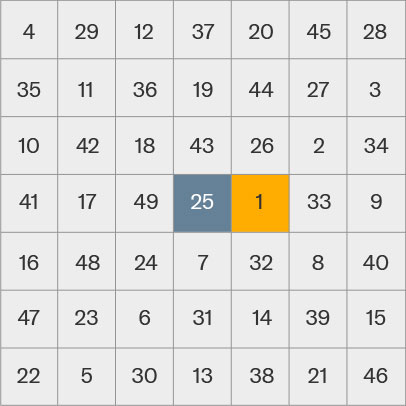

Calder, I. R. F. “A Note on Magic Squares in the Philosophy of Agrippa of

Nettesheim.” Journal

of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 12 (1949): 196–99.

Clucas, Stephen. “Pythagorean Number Symbolism, Alchemy, and the Disciplina Noua of

John

Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica.” Aries 10, no. 2 (2010): 149–67.

Cook, Harold J., Pamela H. Smith, and Amy R. Meyers. “Introduction: Making and

Knowing.”

In Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge,

edited

by Harold J. Cook, Pamela H. Smith, and Amy R. Meyers, 1–16. Ann Arbor: University

of Michigan Press, 2014.

Daly, Peter M. and John Manning, eds. Aspects of Renaissance and Baroque Symbol

Theory,

1500–1700. New York: AMS Press, 1999.

Debus, Allen. The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the

Sixteenth and

Seventeenth Centuries. New York: Science History Publications, 1977.

de Jong, H. M. E. Michael Maier’s “Atalanta fugiens”: Sources of an Alchemical

Book of

Emblems. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969.

Dupré, Sven, ed. Laboratories of Art: Alchemy and Art Technology from Antiquity

to the 18th

Century. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2014.

Eamon, William. “Science as a Hunt.” Physis 31 (1994): 393–432.

Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early

Modern Culture.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Ellison, Katherine and Susan Kim, eds. A Material History of Medieval and Modern Ciphers:

Cryptography and the History of Literacy. London: Routledge, 2017.

Figala, Karin, and Ulrich Neumann. “‘Author cui Nomen Hermes Malavici’: New Light on

the

Bio-Bibliography of Michael Maier (1569–1622).” In Alchemy and Chemistry in the

16th

and 17th Centuries, edited by Piyo Rattansi and Antonio Clericuzio, 121–48.

Dordrecht:

Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994.

Findlen, Paula. “Jokes of Nature and Jokes of Knowledge: The Playfulness of

Scientific

Discourse in Early Modern Europe.” Renaissance Quarterly 43, no. 2 (1990):

292–331.

Forshaw, Peter. “Oratorium — Auditorium — Laboratorium: Early Modern Improvisations on

Cabala, Music, and Alchemy.” Aries 10, no. 2 (2010): 169–95.

Friedman, William F., and Elizabeth S. Friedman. The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined.

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1958.

Glidden, H. H. “‘Polygraphia’ and the Renaissance Sign: The Case of Trithemius.”

Neophilologus 71, no.2 (1987): 183–95.

Hasler, Johann F. W. “Performative and Multimedia Aspects of Late-Renaissance

Meditative

Alchemy: The Case of Michael Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens.” Revista de Estudios

Sociales

39 (2011): 135–44.

Hedesan, Georgiana D. “Reproducing the Tree of Life: Radical Prolongation of Life and

Biblical

Interpretation in Seventeenth-Century Medical Alchemy.” Ambix 60, no. 4 (2013):

341–60.

Helfand, Jessica. Reinventing the Wheel. New York: Princeton Architectural

Press, 2002.

Kahn, David. “On the Origin of Polyalphabetic Substitution.” Isis 71, no. 1

(1980): 122–27.

Karpenko, Vladimír. “Between Magic and Science: Numerical Magic Squares.”

Ambix 40, no. 3

(1993): 121–28.

Lee, Michael Z., Elizabeth Love, Sivaram K. Narayan, Elizabeth Wascher, and Jordan D.

Webster.

“On Nonsingular Regular Magic Squares of Odd Order.” Linear Algebra and Its

Applications 437, no. 6 (2012): 1346–55.

Lenke, Nils, Nicolas Roudet, and Hereward Tilton. “Michael Maier — Nine Newly

Discovered

Letters.” Ambix 61, no. 1 (2014): 30–31.

Leong, Elaine Yuen Tien, and Alisha Michelle Rankin. Secrets and Knowledge in

Medicine and

Science, 1500–1800. Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2011.

Levy, Allison, ed. Playthings in Early Modernity: Party Games, Word Games, Mind

Games.

Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 2017.

Loly, Peter. “88.30 The Invariance of the Moment of Inertia of Magic Squares.”

The Mathematical Gazette 88, no. 511 (2004): 151–53.

Lüthy, C., and Alexis Smets. “Words, Lines, Diagrams, Images: Towards a History of

Scientific

Imagery.” Early Science and Medicine 14 (2009): 398–439.

Moran, Bruce T. “A Survey of Chemical Medicine in the 17th Century: Spanning Court,

Classroom, and Cultures.” Pharmacy in History 38, no. 3 (1996): 121–33.

Moyer, Ann E. The Philosophers’ Game: Rithmomachia in Medieval and Renaissance

Europe

with an Edition of Ralph Lever and William Fulke, “The Most Noble, Auncient, and

Learned Playe” (1563). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Newman, William R., and Lawrence M. Principe. Alchemy Tried in the Fire: Starkey, Boyle, and the Fate

of Helmontian Chymistry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

“Alchemy vs. Chemistry: The Etymological Origins of a Historiographic Mistake.”

Early Science and Medicine 3, no. 1 (1988):

32–65.

———, eds. George Starkey: Alchemical Laboratory Notebooks and Correspondence.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Nummedal, Tara. Anna Zieglerin and the Lion’s Blood: Alchemy and End Times in Reformation Germany.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

Parshall, Karen Hunger, Michael T. Walton, and Bruce T. Moran, eds. Bridging

Traditions

Alchemy, Chemistry, and Paracelsian Practices in the Early Modern Era. Kirksville,

Missouri: Truman State University Press, 2015.

Principe, Lawrence M. “Apparatus and Reproducibility in Alchemy.” In Instruments

and Experimentation in

the History of Chemistry, edited by Frederic L Holmes and

Trevor Levere, 55–74. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

“A Practical Science: The History of Alchemy.” In Art and Alchemy: The

Mystery of Transformation,

edited by Sven Dupré, Dedo von Kerssenbrock-Krosigk, and Beat

Wismer, 20–32. Munich: Hirmer; Düsseldorf: Museum Kunstpalast, 2014.

The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Rampling, Jennifer. “Elizabethan Mathematics of Everything: John Dee’s

‘Mathematicall

praeface’ to Euclid’s Elements.” BSHM Bulletin: Journal of the British Society for the

History of Mathematics 26, no. 3 (2011): 135–46.

“A Secret Language: The Ripley Scrolls.” In Art and Alchemy: The Mystery

of Transformation,

edited by Sven Dupré, Dedo von Kerssenbrock-Krosigk and Beat

Wismer, 38–45. Munich: Hirmer; Düsseldorf: Museum Kunstpalast, 2014.

Reeds, Jim. “Solved: The Ciphers in Book II of Trithemius’s Steganographia.”

Cryptologia 22,

no. 4 (1998): 291–317.

Schiltz, Katelijne, and Bonnie J. Blackburn. Music and Riddle Culture in the

Renaissance. New

York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Sleeper, Helen Joy. “The Alchemical Fugues in Count Michael Maier’s Atalanta

Fugiens.”

Journal of Chemical Education 15, no. 9 (1938): 410–15.

Smith, Pamela H. “Art, Science and Visual Culture in Early Modern Europe.” Isis, 97

(2006): 83–100.

Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific

Revolution. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2004.

“Vermilion, Mercury, Blood, and Lizards: Matter and Meaning in Metalworking.”

In

Materials and Expertise in Early Modern Europe: Between Market and Laboratory,

edited by Ursula Klein and Emma Spary, 29–49. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Taylor, Glenn. “A Secret Message in Dürer’s Magic Square?” Source: Notes in the

History of

Art 23, no. 1 (2003): 17–22.

Tilton, Hereward. The Quest for the Phoenix: Spiritual Alchemy and Rosicrucianism

in the Work

of Count Michael Maier (1569–1622). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003.

Wilson, Robin, and John J. Watkins, eds. Combinatorics: Ancient and Modern. Oxford:

Oxford

University Press, 2013.